Productivity, productivity, productivity: that is the cry we hear from the Chancellor and the Shadow Chancellor.

Raising productivity is the road to higher economic growth, better living standards and improving our fiscal performance, with more room for tax cuts or extra public spending.

With productivity centre-stage, the skills community needs to ask itself how the Treasury thinks about productivity and what is the relative contribution of skills to current and future productivity performance. The answers will determine whether the Treasury is prepared to devote more fiscal fire power to skills – either in terms of more public spending or tax incentives.

Inside the Treasury mindset

Defining productivity

Productivity is defined as output per hour worked.

Output might increase but productivity could remain unchanged. Suppose, for example, an extra worker produces the same level of output working the same number of hours as all those in work. Total output – so-called Gross Domestic Product) will increase but productivity (per hour) will remain the same.

And so, policies which increase the labour supply – including skills training which helps the unemployed or inactive back into employment – can raise GDP but not necessarily productivity. If the people helped produce below-UK-average output, then UK productivity can fall.

Three elements of productivity

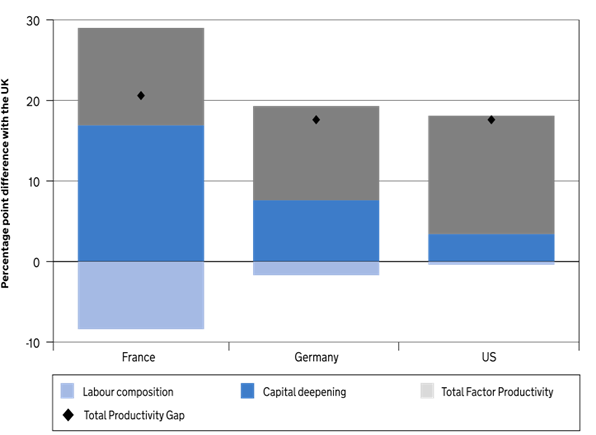

A chart published in the Autumn Statement in November 2023 provides an insight into Treasury thinking on productivity (see Box 1). The Treasury was making a case for doing more to increase business investment.

The chart shows that total productivity is composed of three elements: capital deepening, labour composition and so-called total factor productivity.

Capital deepening refers to both more investment in physical capital and greater use of existing physical assets. Labour composition refers to the skills of the employed workforce. Total factor productivity (TFP) includes work organisation - such as management techniques - and new technology.

Box 1

Chart 4.1: Decomposition of the UK’s output per hour worked gap with selected economies, 2019 cited in Autumn Statement, HMT, November 2023

A very important point to make at this stage is that capital deepening (physical investment) and labour composition (human capital) are both measurable.

But the historic rise in productivity since the Second World War cannot be fully explained by capital deepening and labour composition alone.

There is a residual. This is known as total factor productivity (TFP) - or in ONS usage multi-factor productivity (MFP) – although it is not directly measurable.

Measuring the skills contribution

Underlying the data used by the Treasury in Box 1 is the human capital index of each OECD nation. The human capital index is based on the average number of ‘education years’ of the workforce and the earnings return on an education year.

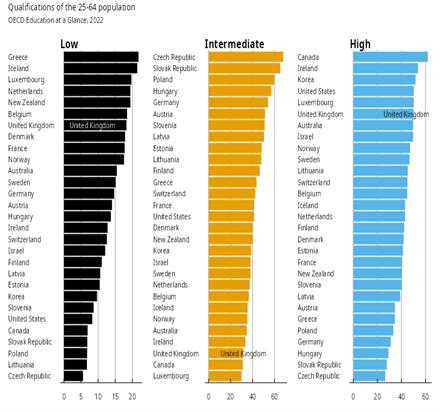

The OECD international organisation produces internationally comparable figures for qualifications. The results for 2022 show the UK has one of the highest proportions of the population aged 25-60 who are highly qualified. By comparison, the UK has a low proportion with intermediate qualifications and a high proportion with low qualifications.

The financial return to qualifications is a key part of Treasury thinking on skills.. Financial returns to high qualifications – especially at graduate level – are high in the UK. The net result of internationally high returns to degrees (and higher level) and high proportions of high qualified in the workforce produces a human capital index that is one of the highest – so the UK has one of the highest human capital index figures in Europe (and higher than the US).

Contribution of skills to UK productivity

Another insight into Treasury can be found at paragraph 4.90 in the Autumn Statement which says:

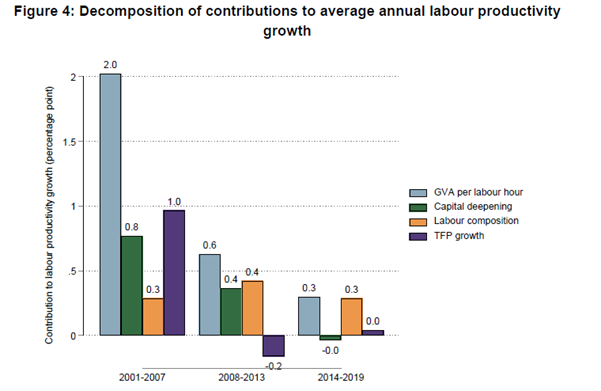

“Long-term investment in human capital is crucial for growth and productivity: changes in labour quality contributed to around 15% growth in labour productivity between 2001 and 2007, and the majority of the labour productivity growth in the years after.”

Box 2

The source for this view is a DfE report – Skills and UK Productivity – published in February 2023. The contribution of labour composition to labour productivity growth has increased over time (see Box 3): 15% between 2001-2007, 67% between 2008-2013 and 100% between 2014-2019. Furthermore, the contribution of labour composition has remained constant at 0.3ppts for nearly two decades between 2001 and 2019.

So, the reason for the increasing proportion of human capital in overall productivity growth is the collapse of the other elements, rather than any increase in the rate of human capital growth. What the Treasury does not refer to is that the rise in the UK’s human capital index (2010-2019) is lower than in most other European countries and major competitors.

Box 3

Skills and UK Productivity, Department for Education, 2023

Skills are a priority but not immediately

Looking at Box 1 again, in 2019 the UK had a total productivity gap of above 20% with France and slightly below 20% with Germany and the United States. Critically, lack of human capital is not the source of the productivity gap between the US or Germany, although it is a factor in terms of France.

In terms of UK productivity, the contribution of skills has been important over the past two decades, but the Treasury seems to have concluded that the immediate priority is to increase capital deepening and the elusive total factor productivity, especially the quality of British management.

Some skills are more important than others

There is also a sense that the Treasury believes that some skills – or more precisely qualifications – are more important than others. High qualifications – using the OECD definition – are what matters for skills to maximise contribution to labour productivity. This is because it is the earnings return on the qualification that counts.

In the terminology of the English qualifications system, the Treasury seems to be more interested in Level 4-8 qualifications than Level 3 and below for adults. The Treasury does not worry, for instance, that increasing amounts of apprenticeship funding in England is for Level 4-7 apprenticeships.

Challenging the Treasury mindset

The German apprenticeship question

The Treasury might, however, be underestimating the contribution of skills to the productivity gap between the UK and Germany. This is because ‘education years’ seems to refer to young people in full-time education and many more young people are on apprenticeships in Germany than the UK. At the same time, the weighting for financial returns will be lower for Germany because apprentice-qualified workers are relatively well-paid.

The international measures used by the Treasury have very little, if any, inclusion of adult skills. This is because the data uses 'education years' which are easier to compare internationally, rather than education levels reached.

The OECD measures provide international comparisons based on the highest qualification level reached, so this is slightly more granular, and will include people who have attained higher qualifications as adults. The OECD does analyse in more detail than is shown in Box 2, but as one becomes more granular, the difficulties of international comparison increase.

The reskilling question

Equally important is that Treasury thinking on the contribution of skills to UK productivity is based on upskilling rather than reskilling: getting people to move up from intermediate to higher qualifications in OECD terms or from Level 3 to Level 4, 5 and 6 in terms of the English qualifications system.

Reskilling is necessary for promoting and supporting greater dynamism in the UK economy. Occupational and sectoral change is a feature of a dynamic economy.

Reskilling at Level 4-5 is only just seeping into Treasury thinking. Reskilling by adults with a Level 4-6 is to be restricted to Level 4-6 under the proposed Lifelong Loan Entitlement.

The idea that an adult with a Level 4-6 qualification might need to reskill at Level 3 or Level 2 is not countenanced. Nor is the idea that adults with Level 3 and Level 2 qualifications might need to reskill at Level 3 and below during their working life.

What is counted for productivity is a person's highest qualification, so, by definition, a lower or same level qualification does not impact human capital.

And crucially, reskilling has yet to be captured in terms of the contribution that skills currently makes to productivity through apprenticeships and adult further education.

The mid-life reskilling question

Recently, the Resolution Foundation has published a report on how to make the UK economy more dynamic (How to Make the UK Economy More Dynamic – Economy 2030 Inquiry). The think-tank recommends that mid-career skills training would provide a further boost to labour reallocation (along with other changes in tax and business support for growing businesses).

Offering adults in mid-life help to reskill at Level 6 and below – not just at Level 4-6 - is something the Treasury should embrace if we are to improve productivity.

Paul Bivand is an independent labour market consultant