The State Pension Age (SPA) is 66. Between 2026-28, the SPA will rise to 67. Less certain is when the SPA will rise to 68.

The 2017 review proposed that the SPA should rise to 68 in 2037-39. The 2023 review was informed by a report by the Government Actuary and an independent report by Baroness Neville-Rolfe. The Neville-Rolfe report recommended the timetable to raise the SPA to 68 should be pushed back to 2041-43. Under current legislation, the SPA is set to rise to 68 between 2044-46.

The debate over when (not if) to raise the SPA to 68 is due to long-term mortality rates and, importantly, projected life expectancy. The uncertainty resulted in the Government deciding to conduct a further review of the SPA within two years of the next Parliament.

If the next general election is held in October 2024, the outcome of the next review of the SPA could be known by October 2026. Abiding by the current rule of giving 10 years’ notice prior to raising the SPA, the earliest it could be raised to 68 is 2036.

Even so, longer working lives and longer retired lives are certain.

Life expectancy from birth

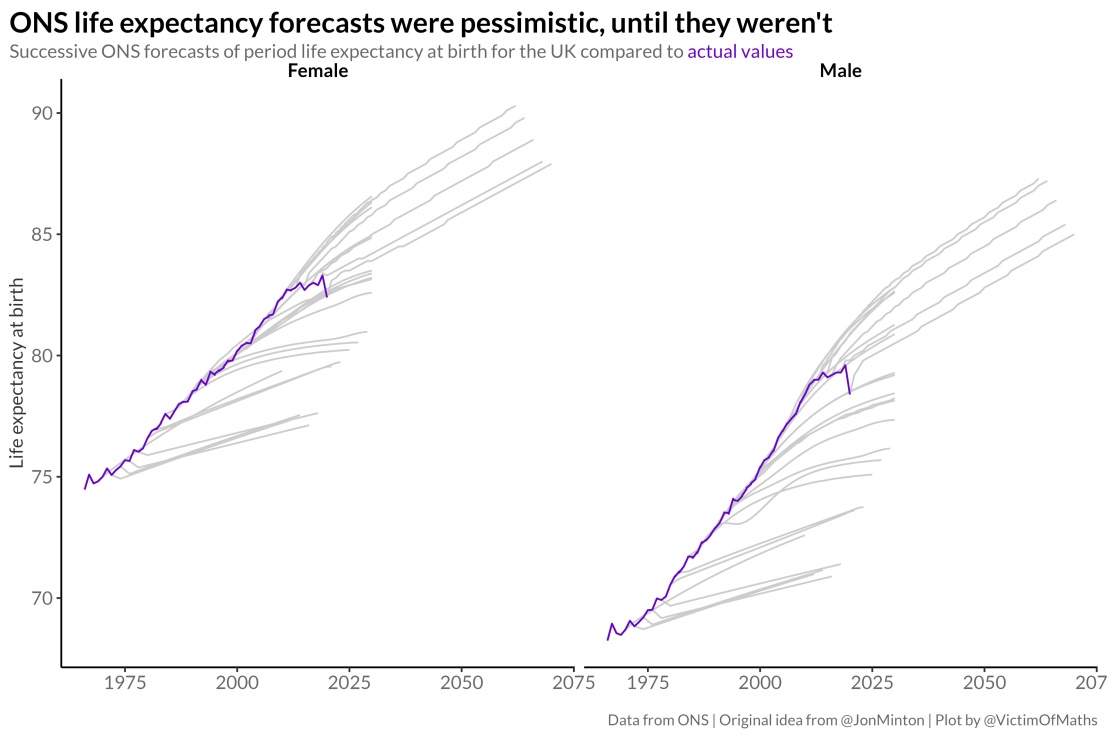

The reason for pulling back on the rise to 68 until 2044-46 is that life expectancy at birth has stopped improving as fast as it had before 2010 (see Box 1). The dip at the end on the purple line is COVID-19. Life expectancy trends are projected to return to the post-2010 trend.

Box 1

Source: Twitter by Colin Angus from Sheffield University (as @VictimOfMaths)

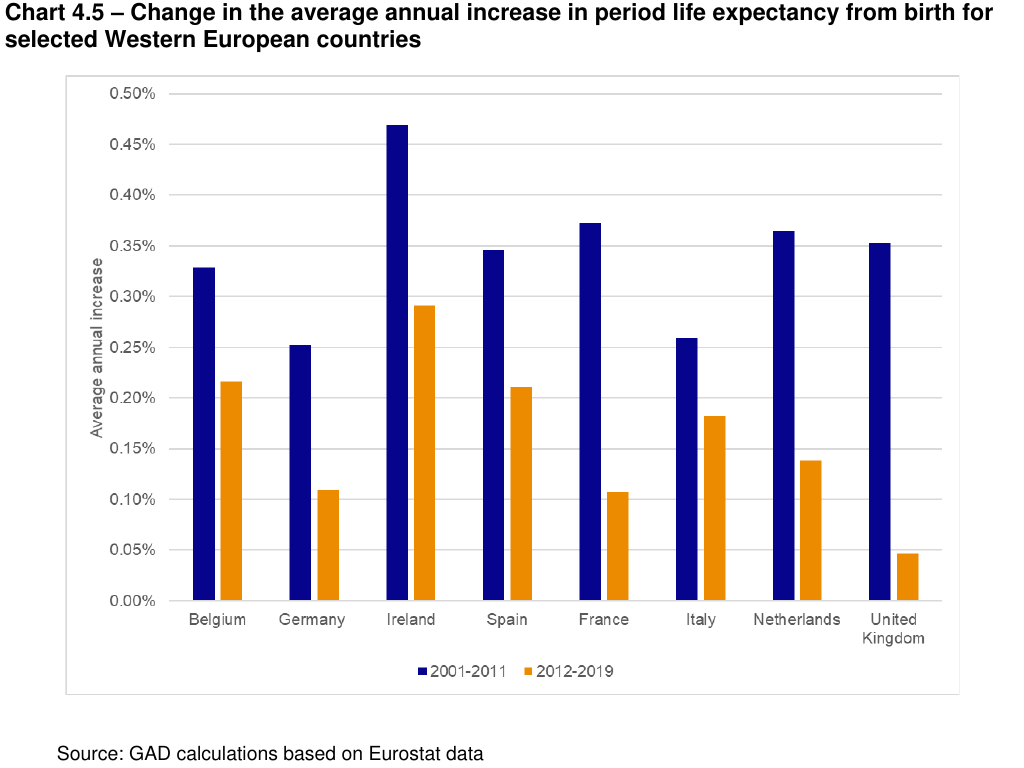

The slowdown in life expectancy is not unique to the UK. Even so, the UK is the worst of the European countries that the Government Actuary looked at (see Box 2).

Box 2

Source: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/state-pension-age-review-report-by-the-government-actuary

Life expectancy from age 65

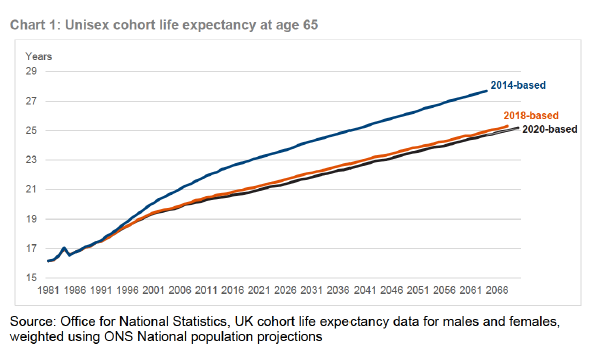

The ONS 2020-based cohort life expectancy projections that informed the 2023 review project that life expectancy will increase over time. Critically, however, the rate of improvement has slowed (see Box 3).

The 2014-based data that informed the 2017 review projected that life expectancy at age 65 would reach 23 years by 2020. The 2020-based data shows life expectancy at age 65 was 21 years by 2020, more than two years lower than previously thought.

Box 3

Source: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/1147389/state-pension-age-review-2023.pdf

Raising the state pension age to 68

Central to review of SPA policy is the average percentage of life that would occur beyond State Pension Age. The rise to 67 between 2026-28 is in line with 31% of adult life to spend in receipt of state pension.

Because of the slowdown in life expectancy improvement, however, there is no case for raising the SPA to 68 in 2037/39. For 31% of adult life to be spent in receipt of state pension, on present life expectancy trends, raising the SPA to 68 would need to wait until 2041-43, or 2044-46 as assumed under present legislation.

Why is the Government concerned about the raising of the SPA to 68?

Spending on State Pension related expenditure was £117bn in 2021/22, more than 11% of total public spending. Spending on State Pension related expenditure is forecast to increase from 4.8% of GDP in 2021/22 to 8.1% in 2071/72. There is a danger that this spending will crowd-out funding in other areas of public spending.

Rising old-age dependency ratios

The state pension is funded out of current taxation on a pay-as-you-go basis. This means the working-age population must meet the cost of the State Pension in any given year.

The World Bank calculates dependency ratios comparing the number aged 15-64 to the total number outside that age-range.

In 2021, the total number of old and young was 57.7% of the number aged 15-64. In 2007, the comparative number was 50.7%.

The UK figure is a little higher than that for high-income countries in total at 54.7%. Some are higher. Japan, for example, which has a substantially older population than the UK, has a dependency ratio of 71.1%. In France, the ratio is 63.1% and Germany, 56.4%.

The age of lifelong learning

Lifelong learning is a generic term for learning through life, including beyond State Pension Age.

For some it means adult skills - skills required to maintain their employability in the labour market.

For others it means adult education - learning which improves the quality of life of adults as well as potentially improving the employability of adults in the labour market.

For adults facing a rise in the State Pension Age when it rises to 67 in 2026-28 and then to 68 perhaps by 2040, they will need both access to adult skills and adult education. Some will be able to continue to work and others will not want to. Those that can need access to adult skills, and the others need access to adult education to ensure a higher quality of life.

Even so, more and more adults over State Pension Age are continuing to work. Although they may receive their State Pension, they are also paying taxes from their labour. Those not working after State Pension Age could still have a better quality of life, with possible savings in health and care budget, by using adult education.

Fifty years of working life

Clearly, discussions about a fifty-year working career need to be taken seriously. When the SPA rises to 67, the working life of adults is 49 years. When it rises to 68, assumed working life hits 50.

Skills throughout life

Over a 50-year span, technologies will change. Old opportunities will decline, and new ones will emerge. Previous episodes of technological change have seen job replacement with new skill requirements. This is the most likely scenario for the future. The new skills needed can’t always be forecast until the technologies emerge and become practical. This means that people will need to learn new skills through their life.

In some cases, this will be continuous professional development within a work area, so that the work becomes unrecognisable after a while. In other cases, people will need to move occupation to new areas and learn new skillsets. It is easier to do this before it becomes necessary, but people and their employers often are not like that.

Accreditation of prior qualifications

Where people have left it until their employer makes them redundant, or goes bust, then there is an issue of recognition of skills. Qualifications, particularly vocational qualifications, are rebranded or reinvented on a regular basis. Hiring managers of employers are not going to understand the skill content of qualifications awarded 30 or 40 years ago, even if they recognise work experience.

With large-scale redundancies, there have been programmes to assess and validate skills so it is easier to get new jobs, with varying success. But with the extension of working age, and continuing occupational change, people will need to reinvent their skillsets, and not just with major redundancies.

Adult education

The second area for lifelong learning is that people who come to realise they might have 20 years of retirement may wish to learn things to do in that 20-year period.

Towards the latter part of that period, there is the bit of lifelong learning that overlaps into occupational therapy (that doctors might use social prescribing to recommend), including much derided courses like basket-making and weaving (that do keep fingers mobile).

Activities that help to keep people mentally and physically active have health benefits too.

Paul Bivand is a Labour Market Analyst