The UK has a truly dynamic labour market. Nearly 1.9m people move into jobs each quarter and nearly 0.7m people start a job with a new employer each month. Understanding such high levels of job changes in the labour market are critical to the design of training policy.

Job changes

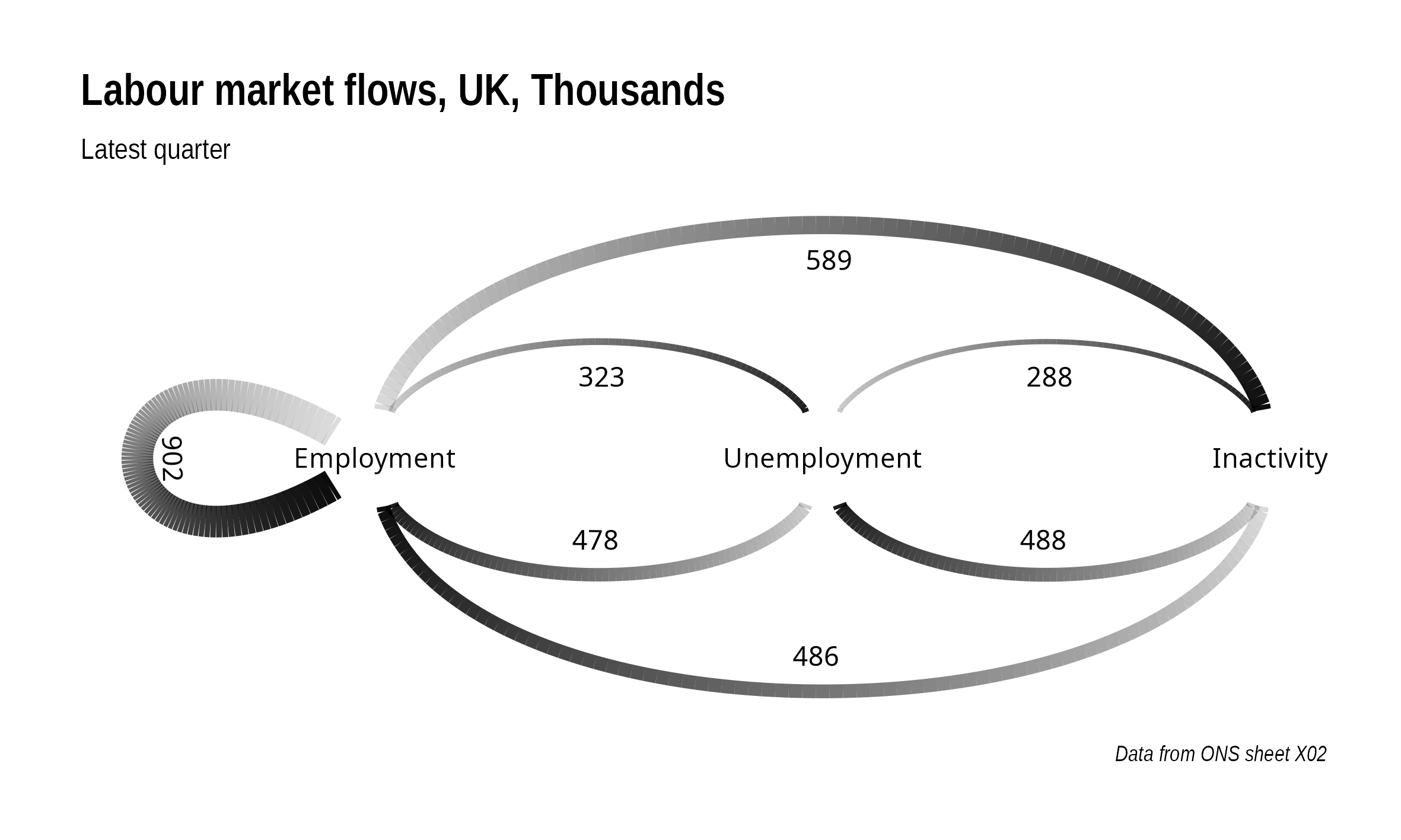

From January – March 2023, over 0.9m people moved from one job to another (see Chart 1). Nearly 0.5m moved from unemployment into jobs and close to 0.5m moved from economic inactivity into jobs.

Chart 1

Note: The dark ends of the lines are ‘to’ and the light ends ‘from’.

In addition, over 0.3m left employment and entered unemployment. A further 0.6m left employment and became economically inactive (including people entering full-time education, deciding to look after their families, choosing to retire as well as becoming long-term sick).

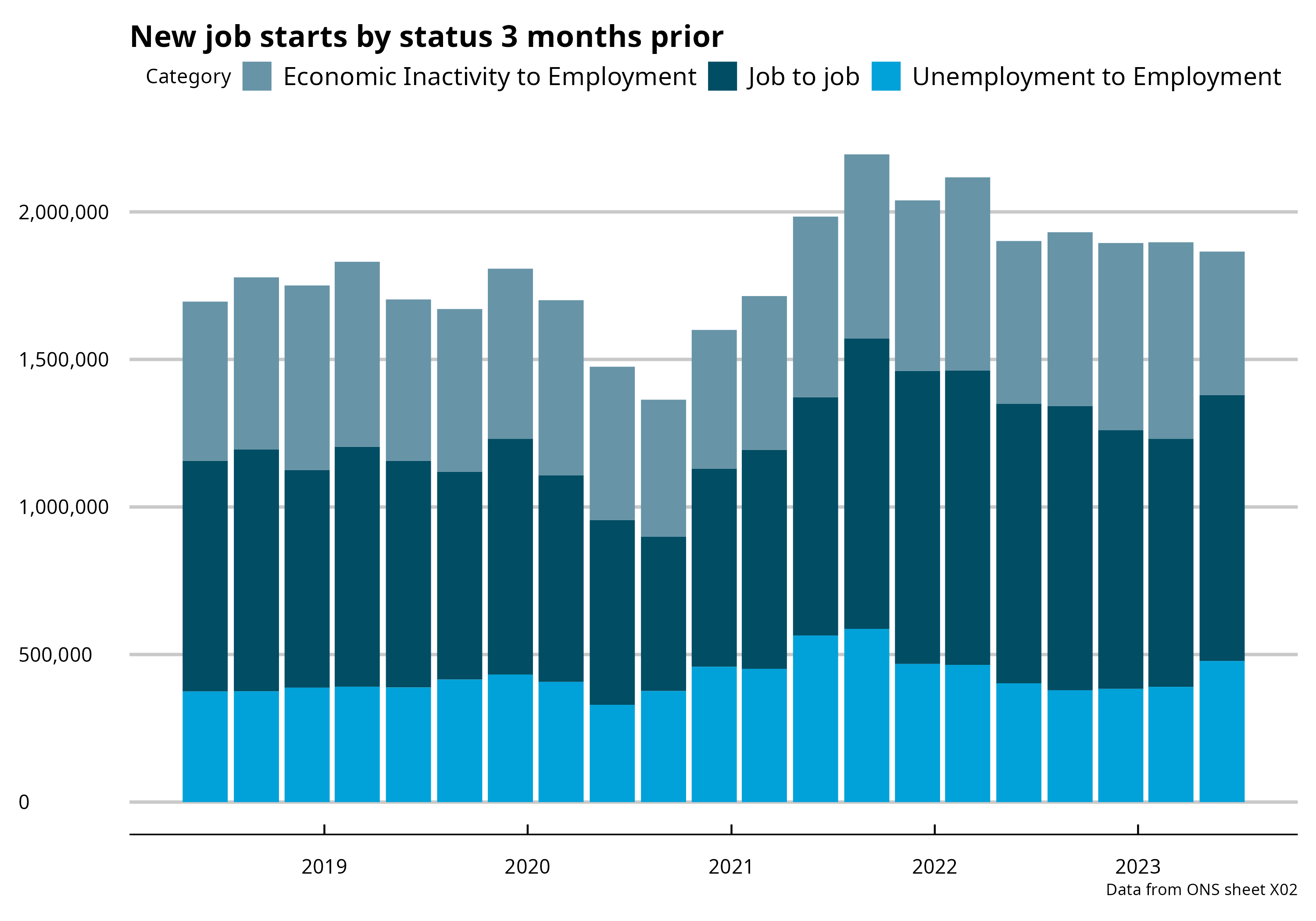

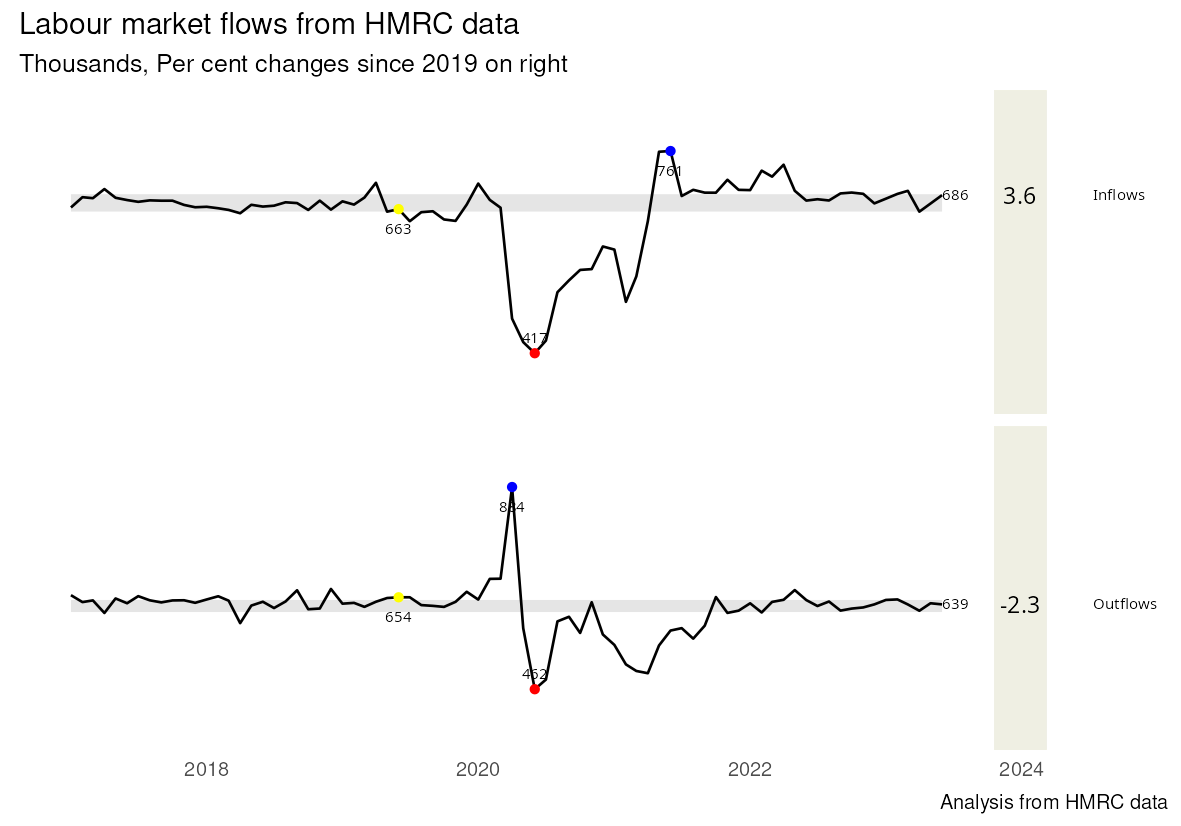

Most job starts are from job to job (see Chart 2). And most job starts are with a new employer (see Chart 3). According to HMRC P45 records, each month, in normal times, between 660,000 and 690,000 people start with a new employer, and slightly fewer leave their employer.

Chart 2

Chart 3

Scale and cost of employer recruitment

These charts show the scale of recruitment that employers undertake. However, the amount of effort that employers make and the cost to them of this scale of recruitment varies. In a ‘tight’ labour market such as we have had post 2021, recruitment takes longer and is more costly than in a ‘weak’ labour market. This has come as a shock to many employers who have not experienced such a ‘tight’ labour market for many years.

Employers recruiting staff look for evidence that a candidate is credible. The information they use includes both specific evidence on skills and evidence of (relevant) experience. Much of HR activity in relation to recruitment is getting employers to define what they mean on both. Sometimes with hilarious results – in tech, requirements for 3 years’ experience of a technology like ChatGPT introduced last year are, regrettably, found all too often.

Pay and job changes

Before the pandemic, people who stayed in the same job had a median pay rise of 3.0 per cent in hourly earnings. If they changed job, that more than doubled, to 7.3 per cent (2018 figures from ONS). However, there was more variation for job changers – the lower quartile for changers was negative 2.1 per cent (stayers 0.0), while the upper quartile of changers had an hourly rise of 23.5 per cent (stayers 8.4 per cent).

Skills and job changes

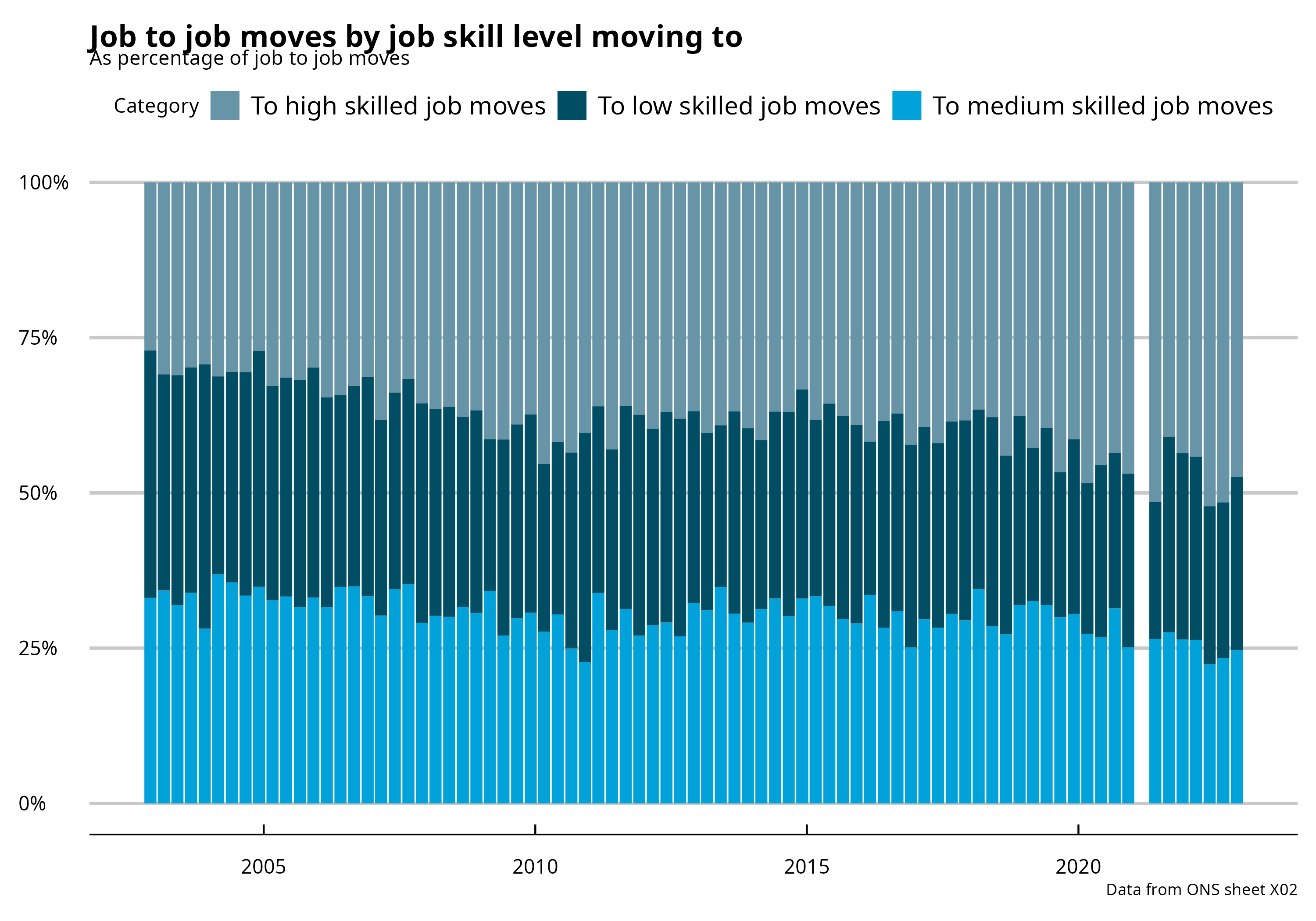

For job-to-job moves, the ONS provides data on the skill groups needed for the jobs people have started in three categories:

- high skilled (managerial, professional, associate professional/technical),

- medium skilled (administrative and clerical, craft skills, personal services such as hairdressing, social care and childcare), and

- low skilled (everything else).

This shows that the share of job-to-job recruitment taken by low-skilled jobs has fallen from around 40 per cent in 2001 to barely over 25% in 2022 (see Chart 4). Medium skilled- job starts have fallen from just under one in three to under 25%. This means that high-skilled job-to-job starts have risen as a percentage from under 30% to over 50%.

Chart 4

Qualifications over the life course

The qualifications young people gain have less and less impact over the life course, as experience takes over. In addition, skills learned as adults are often not validated as qualifications. This means that middle-aged and older adults who find themselves looking for a job because of changes affecting their sector or employer can find themselves with less evidence for new employers that their skills are credible.

Designing training policy

A key question for the design of training policy in the UK in the context of a dynamic labour market and longer working lives is whether the ‘heavy lifting’ should be done by employers or individuals, with the state providing support in the background.

Employer facing training policies certainly have a role to play. Part of their design should include a degree of tie-in after employees have received employer funded skills training, otherwise footloose employees can take these skills elsewhere.

But to go with the grain of a dynamic labour market, most of the ‘heavy lifting’ should be done by adults. But individuals may not have the knowledge or even the apprehension of the skills training they need and, more certainly, the ability to fund speculative skills training.

Strengthening individually driven skills training

There are two ideas politicians should consider in the run up to the general election to strengthen adult funded skills training, one reforming an existing policy and the other, forming a completely new one.

Extend maintenance loans

Adults looking to upskill and reskill at Level 3 and below need help with living costs like their counterparts seeking to upskill and reskill at Level 4-6. Income contingent maintenance loans should be extended to adults on Level 3 and below courses.

Saving for skills

The gap in the market, however, is the converse to income-contingent loans: a savings vehicle enabling people to utilise thrift to amass funds to fund skills training. A national saving for skills scheme based on the auto-enrolment pensions system should be introduced. If an employee contributes towards saving for skills, employers will be expected to contribute as well.

Paul Bivand is a Labour Market Consultant